|

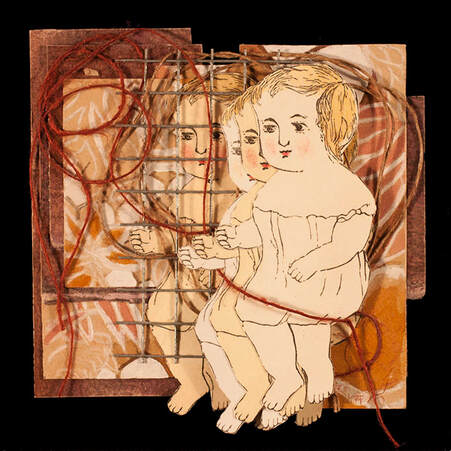

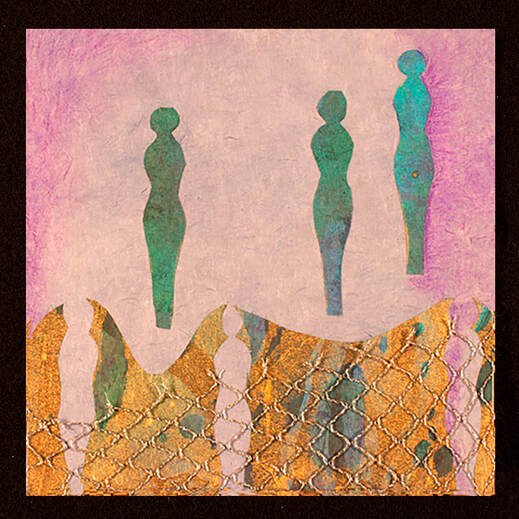

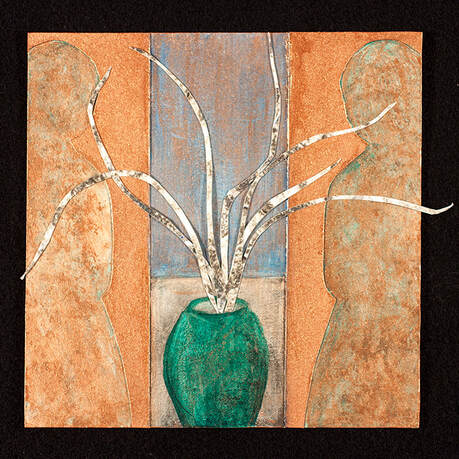

What if two artists, each with different strengths and interests, engaged in a “visual conversation” -- no verbal exchanges, each creating pieces to which the other responds? Another artist and I decided to try. Our experiment shows the Studio Habits of Mind in action. [Spoiler alert: We had this conversation in 2007 and found it so generative that the two of us have been collaborating on artist books ever since. We’re now working on our 12th book.] In my visual arts classes, I’ve used variations of the visual conversation. For example, I’ve had a whole class generate pieces from which students develop ideas for their own work. The Studio Habits of Mind in Action For our visual conversation, my fellow artist and I only specified the size (6 x 6 inch square). Our first images show how differently each of us approached the task, each drawing on interests in our own work.  Image by Shirley Veenema Image by Shirley Veenema My first image reflects my fascination with Joseph Cornell’s poem-like collages (Express, Engage, Understand Art Worlds: Domain) and desire to see what I could create from materials left over from other projects and failed pieces—yarn, wire, an old acrylic drawing, and cutouts from printing mistakes for one of my artist books (Envision, Stretch & Explore). I paid particular attention to ways overlapping layers created a feeling of shallow depth (Observe, Develop Craft: Technique), a bas-relief effect from previous work that I wanted to push further (Stretch & Explore, Develop Craft: Technique).  Image by Mary McCarthy Image by Mary McCarthy For her first piece, my collaborator created a surreal landscape. Her composition of cut shapes, fragments of mesh bag, and single piece of watercolor-stained paper continued her interest in paper collage with repurposed materials. (Engage & Persist, Develop Craft: Technique).  Image by Shirley Veenema Image by Shirley Veenema Considering how to respond to my collaborator’s 2D piece, I imagined how I might create a piece that appeared to be primarily flat while still incorporating relief elements (Envision, Develop Craft). Could I draw with cut paper instead of pencil or pastel? (Stretch & Explore).  Image by Mary McCarthy Image by Mary McCarthy My collaborator too struggled with how to respond before finally settling on a composition of cut paper that incorporated 3D elements similar to the wire and yarn in my piece (Envision, Stretch & Explore, Develop Craft: Technique). A Creative Tension For twenty pieces, the structure of our conversation pushed both of us beyond our comfort zone and stimulated new ways of working (Stretch & Explore, Develop Craft: Technique) --a tension between interests and ways of working that continued for the entire visual conversation. But oh how we struggled! Every time I received a piece from my collaborator, I sighed, “Oh no, flat again.” She did the same upon seeing more of my experiments with shallow relief. Fortunately the conversation structure added elements of play and surprise to our struggles and encouraged us to keep going (Engage & Persist, Stretch & Explore). It also helped us to develop trust in our ability take on new challenges and the confidence that we could work as a team (Understand Art Worlds: Community). In fact, for our most recent book, Madwomen & Angels, we even decided to take on a new challenge: 3D figures. Both of us struggled and not surprisingly, we each came up with a different final solution. After many failed attempts we created seven individual boxes with pockets for small books, and a structure to hold all the individual boxes (Envision, Develop Craft: Technique).  Shirley Veenema brings the perspective of an art teacher (elementary and high school), a researcher at Project Zero from 1987-2007, and a visual artist. Research projects include thinking in the arts, portfolio assessment, technology, and schools using multiple intelligences theory. While an instructor in art at Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, (1980–2015), she served Art Department Chair (2006-2012). Her current work as an artist is in media, mixed media drawing, and artist books. Collaborative media work includes five videos for the show Dangerous Curves: Art of the Guitar at The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and a series of interactive web-based documentaries funded by the Cultural Landscape Foundation. For several years she has followed the work of makers using archives to create work, in particular their use of online digital resources. Her artist book Witches, Magic & Early New England (2016) was produced as part of the Digital Public Library of America Community Representative program to showcase what makers can do with the DPLA online collections. The 5-part book, which tells a story that culminates in the Salem Massachusetts witch trials, has also interested educators looking for alternative ways of assessing student understanding. How to cite this blog entry (APA 6th edition):

Veenema, S. (2020, Jan 20). A Visual Conversation [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.studiothinking.org/blog/a-visual-conversation

2 Comments

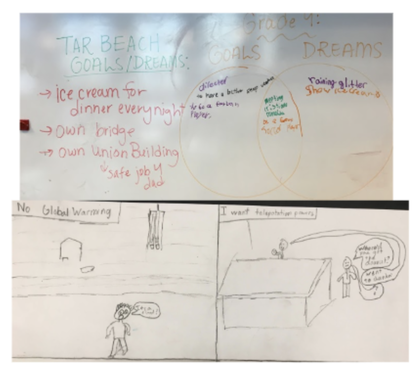

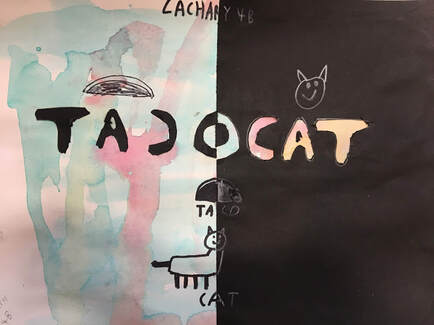

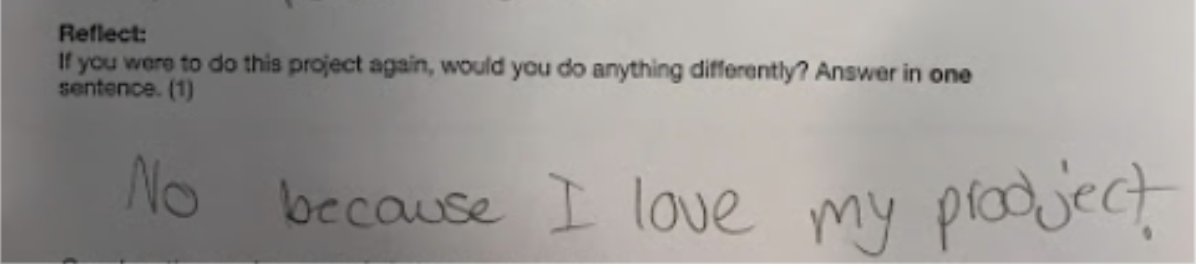

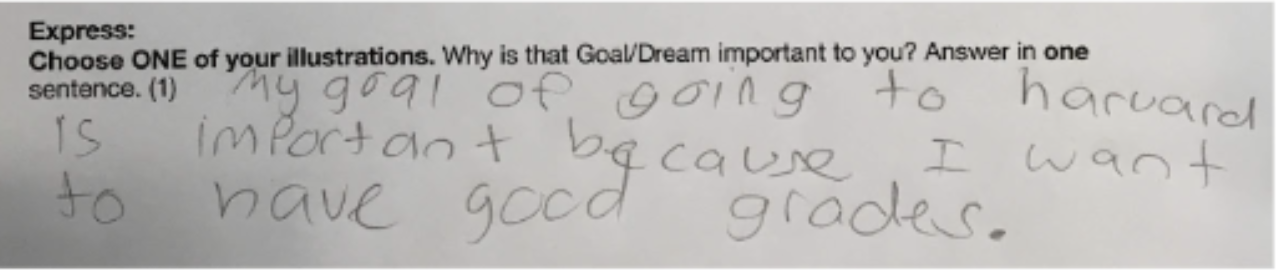

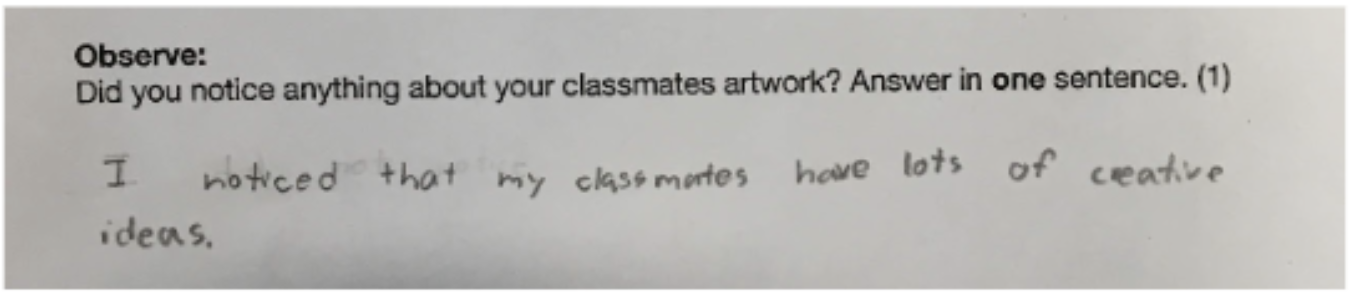

I have always been a huge fan of the Studio Habits of Mind ever since I first heard of them while in grad school at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. I think they are a great way to explain the benefits of an arts education! I love that the SHoM dispositions will not only help strengthen a students artistic practice, but also create skills that can be applied to other areas of life as well. When I started teaching elementary art in Arlington, MA public schools, the SHoM were applied to my curriculum right away. I even developed an activity based on the popular game, “Pokemon GO,” called, “Art History GO;” where I introduced the SHoM to my students in a fun (and silly) way! This past school year, I had the opportunity to work with a talented group of art educators from all over Massachusetts in order to research how the Studio Habits of Mind can be applied to Assessment in the art classroom. In March, we presented our findings at the NAEA Convention in Boston, MA. For my portion of the project, I focused on assessing student motivation. The questions I asked myself were: 1. “What can I learn from my students based on their reflections?” 2. “What type of art project motivates students to create art?” 3. “Does personalization of art projects effect student engagement?” In order to gain any answers to these questions, I created an experiment that involved my fourth grade classes. I had all three groups take part in two art projects. One project was a more personal, expression-centered Artist Book that required students to illustrate their goals/dreams inside. This lesson highlighted the SHoM dispositions, Envision and Express. The other project was more skills-centered, it focused on the Develop Craft SHoM. It involved creating a Positive and Negative Space design with construction paper. After each project, students reflected on their work by using a Self-Assessment worksheet. Through the worksheet, I collected data and was able to observe if one project motivated and kept students engaged more than the other. I was inspired to conduct this experiment after an experience I had earlier in the year when I was beginning a landscape project with a 5th grade class. Before we began, I asked students to describe their favorite landscape in order to brainstorm and jump-start their creativity. This led to a big class discussion in which many students shared places they’ve been; places far away, as well as places around town. Through that discussion I learned so much more about my students that I wouldn’t have known otherwise. After, my students were buzzing with excitement; they could not wait to get started! They carried that excitement with them as they began working on their landscapes. The whole class was so engaged and there was such a positive energy radiating from the room! This was the third and last class I had introduced this project too, I hadn’t facilitated this discussion with the other two groups. It made me wonder, “Would my students have been so engaged had we not had such a personal, connection-making discussion?” During the expression project, the “Goals and Dreams Artists Books,” (as I called it with my fourth graders) we started the lesson by reading, “Tar Beach” by Faith Ringgold. That way I was able to incorporate the SHoM, Understand Art Worlds, into this project as well. We then discussed the main character’s goals and dreams. We also talked about the differences between the two. Students then gave examples of their own goals/dreams. Next, 4th graders brainstormed their goals and dreams by creating thumbnail sketches before tackling the final illustrations and constructing the actual artist book.  To begin the Positive and Negative Space Designs for the skill-builder project, students learned some experimental watercolor techniques and then created an abstract watercolor background. The following class, I presented a slideshow that introduced terms such as: Positive Space, Negative Space, and Contrast. Students then used black construction paper and cut out a shape of their choice. Students then considered composition as they glued the construction paper to their watercolor background in order to display positive and negative sides of their design. In the end, after comparing the reflection worksheets from both projects, I found that I did not see any substantial difference in student motivation between the two projects. I did, however, find that this experiment ignited a lot of motivation in me and my teaching! I learned that personal projects where students have the chance to Envision, Express, and Stretch and Explore, motivate and excite me more to teach than any other lesson. I really enjoy learning about my students and I think it is important to give them the opportunity to incorporate their voice in the art projects I develop for them. A goal of mine as an educator is to create connections with my students so they feel confident and comfortable while making art in my classroom. I want them to look forward to coming back to art class and exploring future projects. I think if my students can see my enthusiasm and see how the Studio Habits of Mind are engrained in my teaching practice, then in turn they will be motivated to create and the SHoM will become part of their artistic practice as well! Examples of Student Evaluation and Reflection:  Samantha Kasle works as an Elementary Art Teacher for students in grades K-5 in Massachusetts for Arlington Public Schools. She graduated from Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 2012 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Illustration. She also graduated from MassArt in 2014 with a Masters of Arts in Teaching. Through her teaching, Samantha hopes to inspire students and demonstrate the wide range of possibilities the arts have to offer. By incorporating the Studio Habits of Mind into her curriculum, students learn to think critically, collaborate with peers, and stretch their abilities to gain confidence and reach their full artistic potential! Samantha is a featured educator in Studio Thinking from the Start: The K-8 Art Educator’s Handbook. How to cite this blog entry (APA 6th edition): Kasle, S. (2019, Oct 2). What Motivates our Students to Create? How Can We Use the Studio Habits of Mind to Assess Student Art? [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.studiothinking.org/blog/what-motivates-our-students-to-create-how-can-we-use-the-studio-habits-of-mind-to-assess-student-art Recently I found myself using all eight Studio Habits of Mind in my daily life. My husband and I are considering downsizing and moving into an apartment one of these days. But we have not yet found the right one. Recently we looked at one apartment and though it was in an ideal location, I felt ambivalent. It seemed too much like a hotel. The style was too new, and I wanted something more artsy, more funky. I wanted the apartment to EXPRESS who I am, and the apartment did not feel like me. So I started ENVISIONING what it would look like if I painted some of the walls in rich colors. That would make it more expressive of someone with an artistic temperament. I envisioned the bedroom with one deep red wall. I envisioned the kitchen in the same way, with one wall deep red, looking out onto the dining room in a medium blue. I found myself trying to decide which deep shade of red I preferred, and asking myself if I could even discriminate among subtlely different shades. Then I started OBSERVING paint colors in photographs of rooms in magazines. I became interested in the field of interior design, and I looked at websites of designers, especially those who used rich wall colors. And so I was in a way using the habit of UNDERSTAND ART WORLDS as I tried to connect my own interior design ideas to those of professionals. I also started envisioning space. Where would everything go? But I had trouble with this, and so I had to cut out little paper shapes and paste them into the floor plan to see how furniture could be arranged. I REFLECTED on this and realized that I was not so good at envisioning spatially and was better at envisioning colors. As I pasted in carefully cut out shapes onto the floor plan, I used STRETCH AND EXPLORE a lot. I kept moving things around trying out different possibilities, experimenting. I also imagined (envisioned) myself spending hours scraping off wallpaper (realizing how ENGAGED I would be, and how readily I would PERSIST in this project because I so wanted my new dwelling to be expressive of my personality. And I thought about how careful I would need to be when painting walls – not my usual impatient impulsive self, dripping paint and cleaning it up later, but instead using STUDIO PRACTICE to carefully prepare for painting, and then applying the paint slowly with care and craft. In the end, we decided against this apartment. But I am so glad we looked at it because it gave me an opportunity to use the eight studio habits without even realizing that’s what I was doing!  Ellen Winner is Professor of Psychology at Boston College and Senior Research Associate at Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education. She directs the Arts and Mind Lab, which focuses on cognition in the arts in typical and gifted children as well as adults. She has written over 200 articles and is author of four books and coauthor of three: Invented Worlds: The Psychology of the Arts (1982); ThePoint of Words: Children's Understanding of Metaphor and Irony (1988); Gifted Children: Myths and Realities (1996); How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration (2018); and co-author of Studio Thinking: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education (2007), Studio Thinking 2: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education (2013); Studio Thinking from the Start: The K-8 Art Educator's Handbook. She has served as President of APA's Division 10, Psychology and the Arts in 1995-1996, and received the Rudolf Arnheim Award for Outstanding Research by a Senior Scholar in Psychology and the Arts from Division 10 in 2000. She is a fellow of APA Division 10 and of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics. www.ellenwinner.com How to cite this blog entry (APA 6th edition):

Winner, E. (2019, Aug 9). Using All Eight Studio Habits of Mind Without Realizing It [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.studiothinking.org/blog/using-all-eight-habits-of-mind-without-realizing-it  We all have relative strengths and weaknesses, and one way to look at those is through the lens of the Studio Habits of Mind. As for me, I’m a pretty good envisioner. I make a lot of plans and love to think through possibilities. And I can reflect, and over reflect, and over reflect on my over reflecting. On the other hand, I could benefit from some better observational skills. That’s something I know about myself generally, but also became really apparent to me as I sat down to watch my queue of YouTube videos recently. I’m a knitter and so my corner of the YouTube world includes fiber related podcasts. This includes the Wool, Needles, Hands podcast by Tayler, a knitter who hand dyes gorgeous yarn and owns an Indie yarn dying business. Recently, Tayler chronicled how she dyes colorways for her Bird in the Hand series of sock yarn sets. Each month, she creates a colorway inspired by a bird. This month is the crowned crane, which is pictured here. I normally look at these bird photos and think, “oh, pretty” and describe it with my short list of superficial adjectives: It’s brown, black, orange. There’s some mohawk action happening. Generally Thanksgiving turkey shaped. And then, eventually… I don’t know... It’s a bird. I see things, but as usual, I don’t see with the same level of detail as Tayler (or really, any other human with eyes) does. My eyes don’t want to slow down and I have trouble focusing on visual images. But within about 30 seconds of talking about the bird photo, she begins her descriptions of the “deep, creamy grey.” And I think, Oh, hey, you know, that is grey. And I guess it is sort of creamy up towards the neck. Then she’s talking about poppy red. Poppy red? I completely didn’t even take in the red details in my first looks. Throughout the five short videos, as Tayler makes decisions about dye colors and techniques, she refers to her inspiration of the bird photos and her close observations of what she sees. Each time I watch these videos, I learn a little bit about how to slow down, how to deeply look, and get practice in noticing new things. For me, those are my weaknesses and so those are the parts of these videos that stick out to me. But observing is certainly not the only Studio Habit to be seen here. Because we see her whole process—from finding inspiration, to making a plan, to using technical skills and content knowledge to make decisions, to experimenting with new techniques, to reflecting on how the yarn has reacted to the dyeing process—we get a chance to see a variety of SHoM in action. Maybe if I were a bad envisioner, I would instead be amazed by the way Tayler plans out which colors she’ll use, when, and in what order. And if I had a hard time engaging in artmaking, maybe I’d instead be fascinated by how something as simple as a photograph can help get me going with my making process. I am particularly susceptible to taking in these observation lessons from watching these videos because I am motivated to watch them. I’m choosing to do so, and I’m engaged. This is what I watch on YouTube for fun, yet because I’m watching a maker, I get to see examples of the Studio Habits, and also practice one of my weaker habits. Not everyone’s a knitter, so yarn dyeing may not be everyone’s cup of tea. But what makers are your students viewing on YouTube? Students can steer you towards an endless array of content that they are already watching. Ask them to find you examples from YouTube, TV, stories they’ve read, that show one of the Studio Habits in action. The Studio Habits are always hiding in plain sight, and we can see them all over the place – in what new places can you and your students find them?  Jillian Hogan is a Ph.D. student in Developmental Psychology in the Arts & Mind Lab at Boston College. In her research, she uses mixed methods to investigate what we learn through arts education and how those findings align with public perceptions. Her primary research interest is the teaching and learning of habits of mind in visual art and music education. She taught for six years in schools that specialize in gifted, inclusion, and autism spectrum disorder populations. When she's not reading or writing, she can be found knitting, spoiling her cats, or playing the piano poorly. www.jillhoganinboston.com How to cite this blog entry (APA 6th edition):

Hogan, J. (2019, May 11). Hiding in Plan Sight...Even on YouTube [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.studiothinking.org/blog/hiding-in-plain-sighteven-on-youtube  Studio Thinking (ST) provides teachers with common language to talk about how we optimize class time – Studio Structures - and the various ways that students work during this time – Studio Habits of Mind (SHoM). The ST language guides conversations with students, colleagues, administrators, and families about the various types of thinking and decision-making that happen during art class. We can share what is happening using the SHoM, a framework to guide our observations and conversations with young artists. The Habits give us starting points so we can target thinking in our conversations with students. When you look closely at Studio Thinking, you can see that it is embedded in all approaches to art education. These thinking dispositions are constantly emerging in your art classes. Though you may call Envision by another name, like “imagine;” or you describe the habit of Stretch & Explore as “trying something new;” most or all of these habits are being practiced every day in your classroom. Use the framework to see which ones you emphasize most and which ones least in order to get an idea of how your students are developing in their artistic thinking. As a TAB teacher, I am quite pleased with how ST pairs with the principles of Teaching for Artistic Behavior (TAB). In TAB art programs, students are self-directed much of the time, following introductions to all available art media. As students initiate their work, making decisions about materials, concept, and purpose, their abilities are clearly visible because they are following their own direction. I recall a student who wanted to make a weaving with his name. He knew how to weave – weaving was a second-grade requirement for all students – and he had joined me in third grade for a mini-demonstration on tapestry weaving with shapes, tried it and liked it. But letters? I feared frustration and disappointment, having attempted this with past students. “Liam, I honestly do not know how to do this. You will have to figure it out on your own,” I told him. He studied the cardboard loom carefully, with its 15-thread warp and turned it horizontally. He blocked out the letters of his name – LIAM - with black yarn over two classes. After all of the letters were blocked in, Liam filled in the background with orange yarn. Another weaver observed his work and asked me to show her how to do this. “I don’t know,” I replied. “Ask Liam to teach you.” Liam’s solution to woven text was so simple and obvious –filling in the entire background after all of the letters were in place. Why hadn’t I thought of that? This is an example of how our students may discover the answers we lack, when they have the flexibility to pursue their own lines of inquiry. Which Studio Habits of Mind did Liam exercise during art class? All of them!  Develop Craft: Technique - Liam’s skills with tapestry weaving improved as he pursued his weaving. Develop Craft: Studio Practice – During studio work Liam accessed his weaving and materials and returned them to the proper locations at the end of class. Envision - Liam started with the concept of his name, in block letters, in a weaving. After the black letters were all complete, he envisioned several possibilities for the background color, settling on orange. Engage & Persist - Liam was determined to pursue his idea, even on his own, when his teacher was unable to guide him in this process. Express - Liam chose bold letters and colors, black and orange, to represent himself. Was Halloween an influence? Perhaps. Observe - Liam had seen examples of weavings and watched a tapestry weaving video earlier in the year. He did not put those techniques to use until he had the idea to weave his name. As he worked, he paid close attention to the spacing of the letters to ensure that they fit, with sufficient space around them for the background color. Reflect: Question and Explain – When Anna asked Liam for help, he explained his process to her and demonstrated the technique. Reflect: Evaluate – Along the way, Liam had to evaluate his progress. He was very satisfied when the piece was completed. In his artist statement he commented: “I wanted to weave my name and my teacher said she didn’t know how to do it and told me to try to figure it out myself. So I did! First, I just did all the letters in black. Then I filled in all the spaces between the letters. The ‘A’ was the hardest letter to do. I really like how it came out.” Stretch & Explore - Liam had to navigate this technique for himself. He studied the warp threads for a long time, then started to weave, making small adjustments as he figured out his technique, especially for the letter ‘A.’ Understand Art Worlds: Domain – Students looked at samples of Navajo weavings, including pictorial rug designs. They watched a brief video clip about tapestry weaving featuring the interlocking stitch to join two colors together. Understand Art Worlds: Community – When Anna asked Liam for help, he immediately agreed to show her how to weave her name into the warp and, in that moment, they became a team. Liam is the type of student who thrives in the learner-directed TAB art classroom, driven by his curiosity and self-challenge. This motivated him to successfully pursue his weaving with high engagement. Even without the lens of Studio Thinking, this much would be obvious. The story of Liam’s progress becomes much more complete when we trace his steps through the SHoM framework, where each of the Habits contributes to his artistic thinking. Being able to talk about these thinking dispositions with students and adults in the school community highlights the value of a visual art curriculum that focuses on long-term growth with artistic thinking dispositions.  Diane Jaquith is co-founder of Teaching for Artistic Behavior, Inc. and a retired art teacher following 25 years in K-8 public education. She directs the TAB Summer Teacher Institute and is an instructor in MassArt's Department of Art Education for the Saturday Studios youth programs. She is co-author of Engaging Learners through Artmaking, The Learner-Directed Classroom, and Studio Thinking from the Start: The K-8 Art Educator’s Handbook. Her blog is titled Self-Directed Art: Choice Based-Art Education. How to cite this blog entry (APA 6th edition):

Jaquith, D. (2019, Jan 15). Studio Thinking and TAB: Happy Partners [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.studiothinking.org/blog/studio-thinking-and-tab-happy-partners Welcome to the newly launched Studio Thinking website! We hope this site serves as a resource for you as you think about Studio Thinking and how it can be used as a lens for viewing the important work that goes in on your classroom. Every classroom is different - student personalities and needs, classroom cultures, teacher priorities and values. . .all of these things make each situation unique. We hope you use the information here as a springboard for creating resources for your particular setting. We created this website with several purposes:

We hope to hear from you! Jill Hogan |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

January 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed